Variations on Themes

Spelunky and games from another future

I wouldn’t be interested in roguelikes if I hadn’t become utterly obsessed with Spelunky sometime around 2008. I am not as obsessed as the fine folks behind the Eggplant podcast1. I guess I am just regularly obsessed, playing the game as best as I can but not going to the internet for lore, tutorials, or any such thing2. This obsession was a bit like my practice of Spelunky3, a portable, casual affair. I played Spelunky almost exclusively on my beloved PSVita when the kids went to sleep, when I was traveling, before I was going to sleep. Even before there were dailies, Spelunky was a daily ritual, foreshadowing my relationship with Slay the Spire.

So I was casually obsessed with this game that had the best of platformers, the best of adventure games, and the best of storytelling without forcing poorly written wannabe cinematic stories down my throat. I loved the art style, the game feel, and the bats (well, I wouldn't say I liked those, but you know what I mean). Winning was great, but losing was even better because it was always memorable, a story to tell those who were smitten. The best thing about Spelunky is those deaths; immediately when they happen, you want to tell your chat what happened because you know they will share the laugh. And you also know you’re sharing something more profound, more necessary than just the story of how you died.

My favorite memory of those days of playing Spelunky happened on a warm summer afternoon someplace in Denmark while I was on holiday. I was sitting outside, playing a casual run, when my oldest kid, who was 4 at the time, started looking over my shoulder, quietly following what I was doing. He had watched me play extensively for the past few months, and while he never wanted to try the game, he was fascinated by Spelunky. So that afternoon, while he was looking, I reached the world 1-4, and after a few seconds of me running around, he said, “Oh, that’s a snake pit level!”. He was right! I, of course, asked him how he knew, but getting a straight answer from a 4-year-old is trickier than an eggplant run, so I soon gave up.

I spent the next few days thinking about that “discovery” by my kid. He had figured out the patterns in the randomizer that create the levels in Spelunky. He had encountered one of the biggest pleasures of playing roguelikes: the moment you glimpse how the procedural content generator works. This pleasure gives players a bit of certainty, a glimpse of other games' stability4. Learning to see a pattern in a roguelike returns that game, temporarily and partially, to the confines of its original genre. In Spelunky, learning which level you are playing allows you to play a “platformer.” In Slay the Spire, learning the patterns returns the game to something closer to a classic deck builder. In Caves of Qud … well, I am not sure what kind of game Caves is, but I’ll settle for role-playing, and that’s what it becomes when we learn to see the patterns.

I have argued that PCG is an essential part of the roguelike as a poetic form. It is the main instrument for creating variation in the genre the roguelike appropriates. From a poetics perspective, what PCG offers is not an instrument for generating content but a way of creating theme variations. Of course, that is content production, but of a different nature. When we think about PCG, we often confine it to instruments that allow developers to create variations of existing things in the game and deploy them as content. That is, algorithms are used to create more stuff that composes the game, from levels to items to even animations. The dream is to have algorithms create the whole game, the whole “content.” I have opinions about that dream, but I won’t write those here.

PCG creates content as part of a poetic form, but that’s its secondary task. What PCG does in roguelikes is develop variations on a theme. The genre provides the theme; the variations are how algorithms can shape that theme into novel forms every time a generator runs. Generators are not magic spells that create a game without one. They result from translating genres, or aspects of genres, into computable rules and then developing algorithmic processes that use those rules to create novel configurations5.

In Spelunky, the platformer genre provides the theme. All the essential characteristics are there: 2D side view, size of the avatar relative to the space, a closed environment with one exit that has to be reached through movement mechanics, and the presence of foes that are dynamic obstacles. Spelunky added a procedural content generation to that mix, a randomizer that created the levels anew for each run. Adopting a rogue system heralded the success of the roguelike as a poetic form, both artistically and in the marketplace6.

I want to focus specifically on the level generator. In video games, a sense of variety on the levels has always been a hallmark of good design, and even landmark games have suffered occasionally due to uninspired levels (hello, Halo CE). However, that variation often required the skills of level designers, creators whose understanding of what players should see when and the rhythm of a game are fundamental to understanding the aesthetic experience of the videogame7. If designers create the systems that players extract fun from, level designers carefully dose that experience over time and make it have a particular perceptual pace. If the game designer is Stringer Bell, the level designer is Boadie8.

Level designers need the psychological insights of game designers but must be able to project them into the constraints of the game as it is played. They must create space and time, action and rest, curiosity and boredom through practical effects, and know architecture and perception. To be a level designer, one must have a taste for the game systems' mathematical underpinnings and the gameplay's architectural flow. Level designers are people with taste.

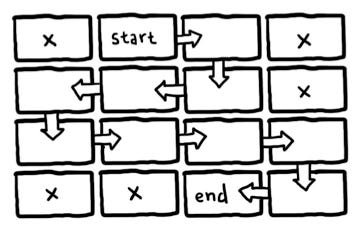

So what happens when that taste is allegedly substituted with a procedural content generator? Spelunky is an example of the importance of taste in game design. Thanks to Darius Kazemi, we have a good understanding of how the level generator works in Spelunky. And that insight provides us with a foundation of taste in the design of generators in roguelikes.

The starting premise is that the aesthetic potential of roguelikes comes from the inhuman variation provided by the PCG system. The generator often creates variations that create engaging, unexpected synergies with other game elements. Even the generator designer should be able to predict only some of the levels that can be made, which is part of the delight of this poetic form.

However, the need for a human to create the levels does not mean the machine takes over. We are talking here about an example of human-computer collaboration. The game designer has some goals that need to be instantiated on the level. Instead of trusting a human with that translator, the designer boils down the principles of a good level into mathematical operations and processes that will create variations around the core idea of fun they seek to express. The generator will create those variations of fun.

So, the fact that no human was involved in creating the levels before play does not mean that the machine has taken over. Computational machines are great creative tools, but they are also pretty dumb (and we are pretty dumb when we think they can think). They only follow instructions and create variations on themes. The themes, with their aesthetic and expressive qualities, are distillations of someone’s ideas and tastes.

These distillations are, however, not exclusively human. For them to work as part of a generator, a person needs to translate them into processes, the form of agency of software. The generalizations and particularizations of a particular ideal of an experience become a collaboration between a person and a software program. In that collaboration, actions translate into what a computer can act upon. From that translation comes the variations. These variations can surprise the designers and players, but they are always part of the choices made by the designer.

This is the most exciting part of computational creativity. I could not care less about machines that can “create.” What I care about is what machines tell us about human creativity. Specifically, how they operate with our cultural heritage and our notion of taste. The Spelunky generator is not just an instrument that creates exciting new levels for exciting new runs; it is a machine’s view of the genre of platformers. It illustrates what we take for granted, what we enjoy, what we find boring, and how we play these games, among many other things. Procedural content generation is not just about creating content but about exploring it, what it means, and why we keep the same games over and over again. PCG is a window towards our creativity, culture, and history; much like Spelunky, it is a machine reflection of all the platformers before it.

Spelunky is a machine that creates variations on platformer experiences, but it is also more than that: it explores how we make people play and how we have made people play. In PCG, there are always people somewhere. PCG is not about substituting the person for the machine but about exploring creativity and worldviews through the automation of game design to create variations on themes.

Therefore, the most critical heuristic in PCG is taste. The designer’s taste will guide the distillation of principles into instructions to unify all variations of a theme into a coherent aesthetic output. What differentiates Spelunky from the experiments in making automatic Mario levels is that the Spelunky levels have an identity. They have a direction, a coherence, and a taste. The output of a good generator, like the one in Spelunky, is the output of a good game design aesthetic sense9.

But there is more to this line of thought. Paraphrasing Pickering once again, roguelikes are video games from another future. The roguelike is not trying to be a film, novel, theatre, or opera. Neither is it trying to be a puzzle. The roguelike is a pleasurable black box, a game designed with a computational agency and experienced with this agent. Roguelikes are what video games could have been if we hadn’t tried to replicate the expressive and production modes of other media. The dominant discourse in videogame design for the last decades is the failure of remediation10. Roguelikes are glimpses of that other future, in which Elite and Rogue became what we all understand as videogames, in which we couldn’t imagine a videogame, a piece of playable software that did not vary, change, adjust, and create new experiences every single time we played with it. These video games from another future would be less about the stories or the worlds and more about interacting with a black box that contains stories, worlds, and many other things, as they mutate and change while we also mutate and change. (In this other future, videogames would be something like Arrival meets VanderMeer, and what a future that would be).

Spelunky is a game from that future, a glimpse into how a computer and a designer see the possible spaces in platformers. It was enormously successful, among other reasons, because it harnessed the unique taste of its developers through the creation of generators and interactive systems that understood some basic principles of platformer fun: the risk, the movement, the kinaesthetic chaos, the clever stupidity of enemies, and the always-present “what if” that gets us to explore worlds created by software…

Spelunky illustrates how procedural content generators are glimpses of how a computer understands and processes human taste. They are software understandings of human aesthetics and human experience, a conversation between a designer and a program, a player and a game, and a game and the history of games that could have been.

One of best game design podcasts out there - listen to it!

Spelunky was my obsession away from my FIFA obsession.

Roguelikes are games you play, but playing roguelikes is a practice. Like a music instrument,like kindness, playing roguelikes is something you do to get better but produce beautiful things and get to know yourself

With stability here I refer to the fact that in many games of progression, the world is stable but challenging, and learning to play is “just” about overcoming those stable challenges that will always repeat themselves. One of the pleasures of play is finding or creating stability in worlds of apparent entropy.

Some people making great work in PCG as aesthetics: Michael Mateas, Gillian Smith, Mike Cook, Younès Rabii, Florence Smith Nicholls.

While I will focus on the PCG aspect of Spelunky, the combination of secret-based gameplay and PCG made this game a landmark. Many other games in the past had secrets as part of their gameplay or had PCG. However, the combination of both elements is a core part of the experience of the game. In the extended version of this text, which I may publish here but will be part of the final book, I will explain the importance of secrets as a creative understanding of black-boxed systems and how Spelunky may also be a relevant piece of computational culture, in these days of Big Data AI.

Credit: everything I know about level design comes from the brilliant Robert Yang.

Alright, here’s a less criminally obscure analogy: If the game designer is the composer, the level designer is the director.

Yes, there are exciting avenues for increased automation here: what if the levels were the output of a large model trained on many platformer games? Wouldn’t that also be “taste”? Yes, of course. Taste is a cultural aggregation of what we have experienced, filtered through personal experience. So, the machine model, I imagine, would have at least the first part of the “taste” concept. However, it would lack the second unless the selection of those datasets is understood as “personal experience.” Which, of course, they are. So, automated game design could be a matter of taste when selecting datasets for training the generators. One of the failures of AI Dungeon is precisely this lack of taste, the vulgar amount of stuff it diluted that made it initially an excellent toy and ultimately a failed experience. I think some of the most exciting researchers in this topic advance approaches similar to these – and those are people with taste.

With some exceptions: for example, Doom was a significant appropriation of Man With the Movie Camera for the computational era, a genuinely novel experience through truly novel technology.