A clever pun about puzzles

Avoiding a verb while expressing an opinion

Puzzles are not games. This is mainly an opinion based on a fact: I don’t like puzzles1. Every time I see a puzzle in a video game, I sigh. Occasionally, in those games where puzzles make sense, I solve them. I sometimes even enjoy them. Most often, I end up dropping the game and finding something new.

Edit: a great game scholar, Veli-Matti Karhulahti, wrote in 2013 a paper on exactly this topic: Puzzle is not a game! Basic structures of challenge. It’s a great text, and readers interested in this topic should start by reading it!)

I think puzzles are the lazy solution to making a game. I’ve seen it in uncountable student games and sometimes professional games: to create a core gameplay loop, let’s make a puzzle that fits the game's mechanics. Then, the player uses their skill within the boundaries of the mechanics to solve that puzzle2. Fun is being served.

Worse, sometimes designers find a really engaging interaction loop, a profoundly pleasurable series of actions and feedback that players and systems do together, and they slap a puzzle onto it to turn it into a game3.

There’s an even worse case for my aesthetic sense. One I understand but dislike. The puzzle is a poetic form. If, as I’ve argued, the roguelike is a lyrical form of the videogame, the puzzle can also be considered poetic. I think The Witness is explicit about this interpretation. But of course, from my radical, intolerant perspective, this understanding turns “games” into “puzzles,” a different aesthetic and cultural category4.

I know I’m being obnoxiously formalist about it, so I’ll give a vague, liminal explanation of what I mean. In their most reductive meaning or the poetic form of understanding, puzzles are not games because we don’t play them. We complete them, we finish them, we solve them, but we don’t play them. There is no play in puzzles. Or, at best, there is the same understanding of play as the “play” in a manual gearbox5.

Strict puzzles constraint action until it fits in patterns of trial and error, with limited forms of success. I understand why they are so tempting and enjoyable for game designers: puzzles can be so strict in shaping human action in a game that they lead players to the desired outcomes designed by their creators. They are analogous to well-designed objects, the kind of doors Donald Norman6 loves because they tell us how to operate them. Puzzles are ways of containing strict formulations of fun.

Alright, maybe not all puzzles. I like puzzles in games of emergence, in playthings constructed by stitching together systems in ways always verging on the chaotic. A puzzle is a great expressive resource in games in which puzzles can be solved using many other systems. Puzzles in the recent Legend of Zelda games mostly showcase the systems' design, which I find pleasurable because they can be solved by playing7. And they can be played “wrong”.

So, there are two types of puzzles. One, the poetic form, wants to convey meaning; it’s a direct conversation between the designer and the player, and it ends in a nod of approval from the creator to the player: "You have solved this; well done.”

The other, the chaotic form, is an obstacle a player must solve using any systems or tools provided to the player in ways not prescribed by a previous design. It is a dance with systems.

The first type of puzzle appropriates games and parasitically turns them into something else we don’t play with (can you notice I don’t like them?). The second type creates forms of play that have success criteria, win/lose conditions, and emotionally satisfying outcomes by putting the player up front and central.

My love of roguelikes (and sports8, open gameworld games, and some interactive narratives) stems from the fact that they don’t easily accommodate puzzles of the first kind. These are all the kind of playthings we like to call games, the kind of things I like playing with.

Maybe that fact is also an opinion.

Another case I don’t want to deal with here is the puzzle turned into the “game” added to an interactive story. Look, I have a beed with Stray. I love cats. I would love to play a game in which I am a cat, a lovable asshole who is an agent of chaos. But the cat in Stray is the least cat a cat has ever been, all because it is just a vehicle to solve puzzles to tell a story. Write a book, draw a graphic novel, let me be a damn orange cat, please.

Later on, I will praise the Zelda games, so let me say here that the dungeons in these games are clever abominations, even if occasionally fun.

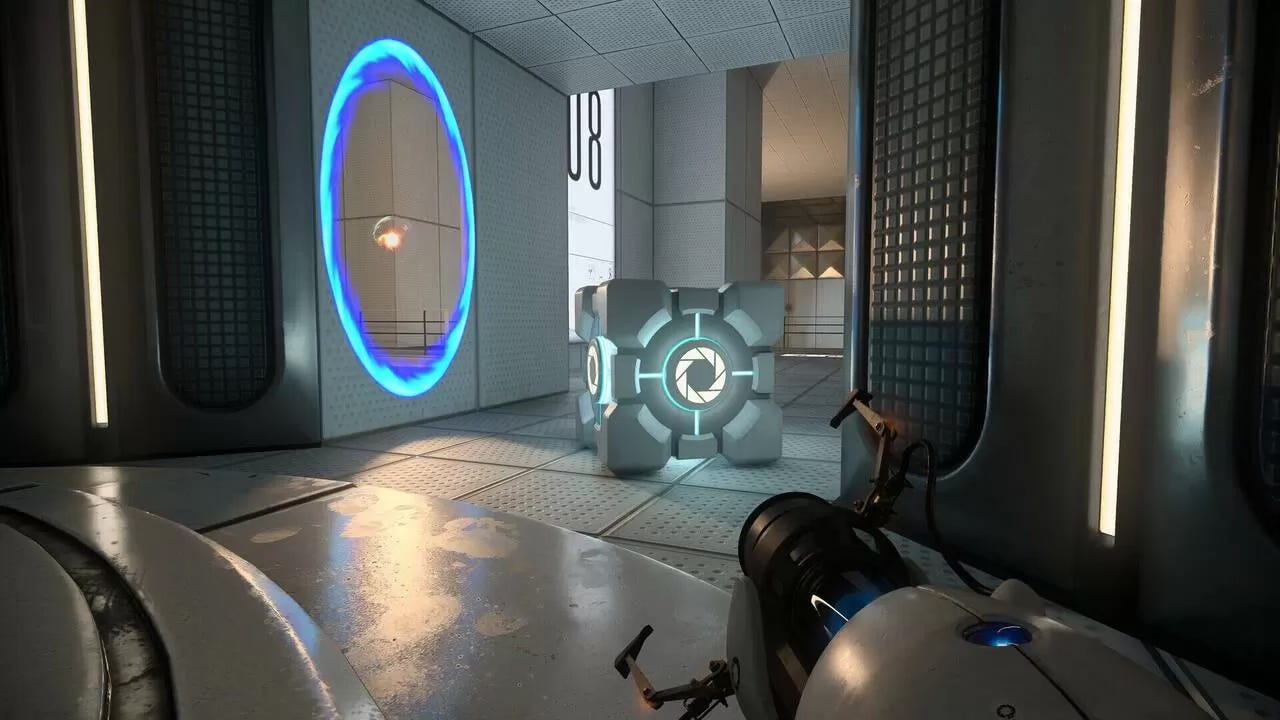

Portal? Damn, Portal is the same. With two redeeming factors, the core loop is enormously fun because of its extraordinary game feel. And the writing is excellent. By the way, Portal is a puzzle with a superb game feel, which is a fantastic way of designing puzzles even if they are not games. I like puzzles that feel like games. I like being deceived.

Manual gearboxes are the Portal of transportation forms. Puzzles that feel like games. Consider this if you ever hitch a ride with me in a manual car.

Norman doors are such a thing that there’s even a 99% Invisible video about them. That video says so much about contemporary game design it’s almost painful. But of course, as Liz England argued, game design is about the door problem. None of this justifies the hours I’ve spent looking at these videos for research, of course.

Like the great Nifflas does with the newest Zelda game, solving puzzles in the rightest bestest ways.

If you’ve gotten this far, it is probably because you know me and expect a football reference. So here is Cruyff explaining how football is a puzzle (of the chaotic type).