Welcome to the first Playing Software monthly edition! On the menu today we have videogames, artificial intelligence, game engines, and one last thing.

Too much videogame

Once in a while, I stop playing Slay the Spire and I try out a new game or two, to check out what I am missing. So when I looked around to see what’s out there, Dave the Diver caught my eye. Yes, I know I know, there's all the Starfields and Baldurs and other shiny things out there. But those look overwhelming, and I'd rather go diving. So Dave it was!

And ... sure, it's a great game. Lovely visuals, good writing with a decent sense of humor, solid but not great game feel, ... But I quite don't like it. And at first, I couldn't understand why. On paper, it has everything I should like in a game. And yet, as much as I tried, I still couldn't get myself to enjoy it.

Then I realised it. There's too much videogame in Dave the Diver.

So, I'm not going here into whether a videogame needs to have many hours of gameplay for being "worth it". After all, one of my favorite games is Queers in love at the end of the world, which does in 10 seconds what some studios need years of development and thousands of workers to achieve. It's not the hours, it's the amount of videogame!

In Dave the Diver, there is an action game that involves diving and fishing. Then there's another game in which we are serving dishes at a sushi bar. Both games have management loops attached to them: the bar gives money that can be used to invest in the bar, or in gear to go diving. There are also fake social media apps one can keep an eye on, characters to keep happy, quests, narratives, challenges, events, ... Everything is there. And everything, for me, is too much.

From a game design perspective, Dave the Diver is excellent. It's a game constructed around two very tight core loops, fishing and serving dishes, that have a number of secondary loops connected to them - from caching specific fishes to grinding wasabi or serving beer. These loops are then modified by other loops - what I have tried to describe once as metagames. In Dave the Diver, everything is part of a game loop, or relevant to a metagame.

That is exhausting.

Despite all I've said in the past, I actually quite like videogames. Just not when there's too much videogame in them. When in a videogame is nothing that is not an explicit, quantized, instrumentalized part of a loop or a metagame, it has too much videogame. If there's a lot of calculation, if there is a need to situate all player action within the logic of rationally reaching the goals of the game that have been clearly explained to me, I quit.

Almost every videogame player loves this: the pleasures of all actions being recognized as being meaningful in the game. The clear acknowledgement of progression as we become better at playing the game, an artform in itself. I get it! That's the fun and the beauty of games, for many. Just not for me.

I love games because I get to play with them, because they are alibis and excuses to try things out, to explore, to think, to express myself. But I don't need the validation of a system, or worse, of an implicit designer, to get there. I want things to happen, intended and unintended, recognized or not. It's not just emergence, it's the fact that I want to play so I am part of making the loops, so I am part of making whatever I actions I take in the game meaningful and important. I don't care about the videogame acknowledging me. Hell, i'd rather the game ignores me, or directly hates me! There's a more interesting playful relation there than in all achievements still locked.

Game designer extraordinaire Doug Wilson often quotes this fantastic sentence from the arcane kids manifesto:

"the purpose of gameplay is to hide secrets".

That’s exactly what makes games and game design interesting. If gameplay has no secrets, if everything is part of, revealed by, or quantised through a system or an achievement or a loop, there is no gameplay. It is just ticking boxes, a form of bureaucratic play.

In the classic should-be-read-as-a-game-studies book The Utopia of Rules, David Graeber writes:

"Games allow us our only real experience of a situation where all [...] ambiguity is swept away. Everyone knows exactly what the rules are. And not only that, people actually do follow them. And by following them, it is even possible to win! This, along with the fact that unlike in real life, one has submitted oneself to the rules completely voluntarily, is the source of the pleasure. Games, then, are a kind of utopia of rules." (p. 194).

This may sound like a good thing. Except if we continue reading, and we follow Graeber's reflections on the importance of play, he states that play is "a principle that generates rules, but is not itself bound by them" (p. 197). That utopia sure sounds less exciting.

To me, gameplay that hides secrets is what keeps me going back to a game.I loved the world of Proteus because it was indifferent to me, the player, arrogantly trying to find the quantised meaning of what I was experiencing, until I gave up and let go and enjoyed the game. Even a game where all actions are part of systems of systems, like Spelunky, carefully hides secrets in those systems, like the eggplant. Designers should do more eggplant systems, hiding the mechanisms that makes us have fun.

Dave The Diver, with its insistence on having every single action we can take as players be part of a system, be quantized and reduced to instrumental decisions, is bounding play to rules, and there are no secrets anymore. It becomes a form of bureaucracy, a binding of play to the compliance of rules.

And as Graber puts it,

"What ultimately lies behind the appeal of bureaucracy is fear of play" (p. 196).

Because software is now everywhere and in everything, we have become used to being quantized and calculated. And our videogames had never a chance to resist, as they are so adept to convincing us about the pleasures of rule following. But what we have lost is the mystery, the secrets, the play that reveals why we actually care about the game loops.

The only true videogame is that which refuses being too much of a videogame.

Yesterday, on AI news

I really don't want to write that much about AI right now. The craze around the GPTs and the MidDiffusions is slowing down, but there's still a lot of interesting things going on around generative AI. Here are my 2 takes for this month:

My opinion of the month: The best examples of generative AI will happen when systems that are not intended to work together are forced to work together. Sure, generative AI sitcoms are interesting. But, what would Lynch do? Many AI expression explorations are fairly vanilla, paint-by-numbers (pun intended) approaches to doing with the tech what the tech does best. The future will always be where we force the tech to do what it does worse, in meaningful ways.

Weizenbaum is doing a comeback! Ben Tarnoff wrote a nice piece about him for The Guardian, and there's a good text in Science about "the need for a Weizenbaum test for AI". This is great news, as Weizenbaum's legacy is often reduced to ELIZA, when he was a pioneer of the ethics of technology. In fact, there is a Joseph Weizenbaum Award in Information and Computer Ethics (while all the awardees deserve it ... are there other than men in Information and Computer Ethics? (spoiler alert: you bet! - and not just, there's many more). Weizenbaum's Computer Power and Human Reason was central for making the second half of Playing Software a more coherent mess than the first part. I'd say that all the work I am doing now in ethics and AI and play is basically annotating Weizenbaum in a playful mood. So it's good to see that it's not just me who thought that's a work worth revisiting!

One last thing

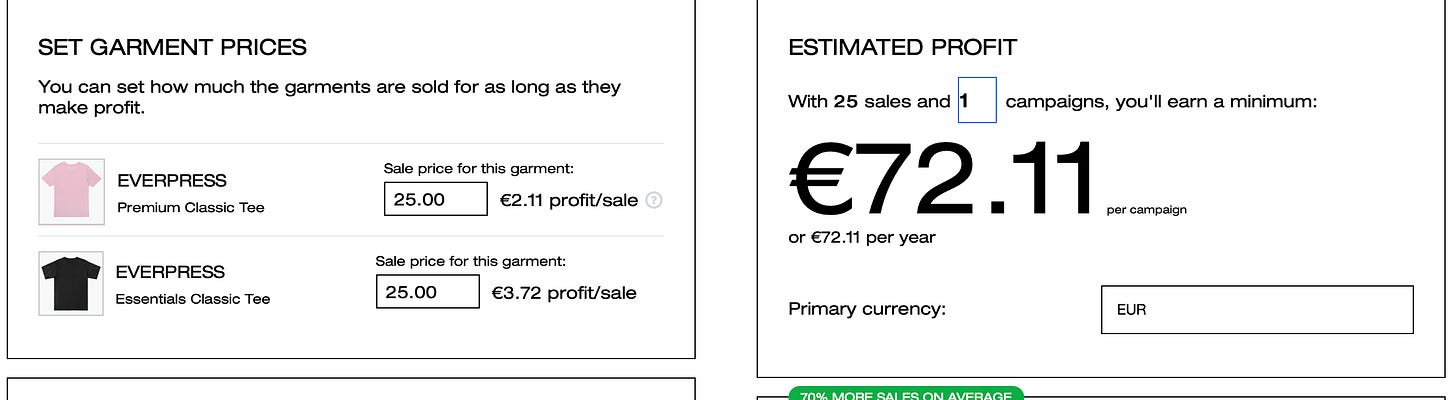

If you are interested in showing your concerns about generative AI, now you can do it by wearing a t-shirt! I have started this Everpress campaign selling t-shirts. As you can see in the following images, I won't be earning that much money, and all the proceedings will go to Open Arms, because not only it does help people who would otherwise die, it also annoys quasi-and-full-on-fascist people in Southern Europe, which is a life goal.

I don't have the rights to the band that is subtly alluded to in the t-shirt, so if I receive a cease and desist, so be it.

I will be back some time in October with more thoughts about play, artificial intelligence, and whatever else I find interesting to rant about. Stay safe!