Here’s an idea: the roguelike is a poetic form.

In poetry, form describes the formal structure of a poem, its rhyme and verse length, for example. Sonnets are a poetic form, like epics or haikus.

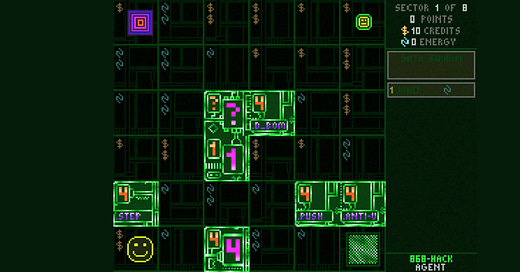

Roguelikes are a poetic form of videogames. Spelunky is the poetic form of the 2D scrolling action game. Into the Breach is the poetic form of the turn-based strategy game, and Slay the Spire … well, you see where I am going. Roguelikes are ways of structuring particular videogame genres for poetic effects.

Yes, I mean here “aesthetic” effects, but I honestly don’t care about aesthetics just yet. I want to connect the roguelike with a genealogy of poetic forms. To me, roguelikes are as close as we have in videogames to sonnets, novellas, or three-act plays. They are a form we use to create specific experiences with videogames.

Of course, working with the concept of poetic form requires specific formalisms. The roguelike as poetic form has particular attributes, like the sonnet or the novella. While I like the Berlin interpretation and all its derivates, I am taking a different, more minimalist approach. The roguelike as poetic form is defined by:

- Permadeath: when players die, their run is reset, and they must start again. Sometimes, the game keeps the progress state; sometimes, it doesn’t, but death is death. Therefore, there is something at stake in every choice and every action.

- Procedural content generation: the roguelike is the outcome of a collaboration between human and computational agencies. A series of algorithms will produce some of the game's content, adding variation to different elements, from levels to objects. The generation is communicated (“the walls are shifting”) but not explained, requiring play to understand how the generation works.

- Secrets: roguelikes hide information and require explorative and appropriative play to master their challenges. The eggplant in Spelunky or the infinite combos in Slay the Spire are my examples. I prefer to use the concept of “secrets” because, as the Arcane Kids manifesto puts it, “the purpose of gameplay is to hide secrets.”

I find this way of thinking about roguelikes fun and productive, mainly because it helps me understand why these games become obsessions for me: like a poem, a song, or a movie, roguelikes get stuck in my consciousness and refuse to leave, and it makes me crazy not to know why. At least now I have an idea to start working from.

I will explore these ideas during my sabbatical at the MEDIUM research group at Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. I’ll be giving talks with parts of this work in progress throughout the year, so for anybody in Spain, stay tuned!

Great write-up!

"I find this way of thinking about roguelikes fun and productive, mainly because it helps me understand why these games become obsessions for me: like a poem, a song, or a movie, roguelikes get stuck in my consciousness and refuse to leave, and it makes me crazy not to know why. At least now I have an idea to start working from."

-> This makes me think of Derrida's conception of a poem as that which gives rise to the desire of "learning by heart." The downbeat, the birth of rhythm, etc. Or Northrop Frye, the "hypnotic incantation" that one cannot resist.

I'm eager to hear how your thoughts on the poetry lens continue to develop!